Sport

Somalia is rebuilding its education system from the ground up, funding teacher salaries with domestic revenues, implementing a national curriculum and reopening schools long silenced by war.

Imagine an entire generation growing up without knowing what it feels like to sit in a classroom, much less have access to an education that billions worldwide take for granted.

Fifteen years. That's how long schools in Harardhere, a coastal town in central Somalia, remained shuttered under the shadow of the gun.

When the chatter of schoolchildren returned to these empty classrooms in 2023, it was as much a reflection of conflict-ravaged Somalia's resurgence through education as Harardhere's reclamation from the clutches of the terrorist group Al-Shabab.

Somalia's scars run deep. For decades, civil war and terrorist violence systematically dismantled what was once a thriving education system.

In the 1970s, Somalia allocated nearly half its national budget to education, pioneering mobile schools for nomadic populations and blending Islamic curricula with a modern syllabus. By the beginning of the millennium, the system was in ruins.

"Recurrent violence would shut down our schools, leaving us uncertain about when – or if – we could return," Abdi Samet, now in his early 30s, tells TRT Afrika.

His words mirror a reality that millions of Somali children faced. School playgrounds became battlegrounds. Teachers fled. This was due to Al-Shabab’s deadly terrorist activities.

With no unified curriculum, schools pieced together a syllabus from what was being taught in parts of Egypt, Saudi Arabia, or India. Expensive private institutions were the only option for families who could afford them. Teaching materials were scarce, and qualified teachers even scarcer.

Amid the devastation and the hurdles, Somalis refused to abandon education. Communities set up makeshift classrooms in borrowed spaces.

Private universities, such as SIMAD Institute (now SIMAD University), opened their doors in 1999, offering higher education when the state could not. The Somali National University reopened in 2014.

"My father was my greatest support," recalls Abdi. "He went above and beyond his means, creating a learning environment at home despite the obstacles we faced. His dedication was my lifeline, giving me the strength to push forward. He taught me subjects I struggled with or arranged private tutors to help me improve."

Turning point

The past three years have been marked by dramatic changes in Somalia's education system.

Under President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud's administration, education has moved from the margins to the centre of national policy.

The numbers tell a story of both challenge and progress.

"When we assumed office less than three years ago, a paltry 900 teachers were on the government payroll, less than 25% of children were enrolled, and over four out of five million children were out of school," says education minister Farah Sh. Abdulkadir Mohamed.

In just two years, the education ministry recruited 6,000 trained teachers and deployed them nationwide. The goal is to reach a teaching workforce of 12,000 by 2026. Crucially, teachers' salaries are funded by the national exchequer, not foreign aid.

"Our teachers being paid entirely through domestic revenues signal a transformative shift to national ownership and self-sufficiency," says Farah Abdulkadir.

President Hassan Mohamud frames this as an acknowledgement of their "indispensable role in shaping our human capital".

"For too long, Somali teachers' tireless dedication went unrecognised. We have resolved to recruit more teachers. They are the heartbeat of our nation, architects of its future, cherished and prioritised by my government," he says.

The national education budget has more than tripled, from 3% to 9.4%, over the past three years, funding school construction and rehabilitation across all federal member states.

"We are investing not just in buildings; they are symbols of recovery, inclusion and hope," says Tata, an official involved in the initiative.

Building systems

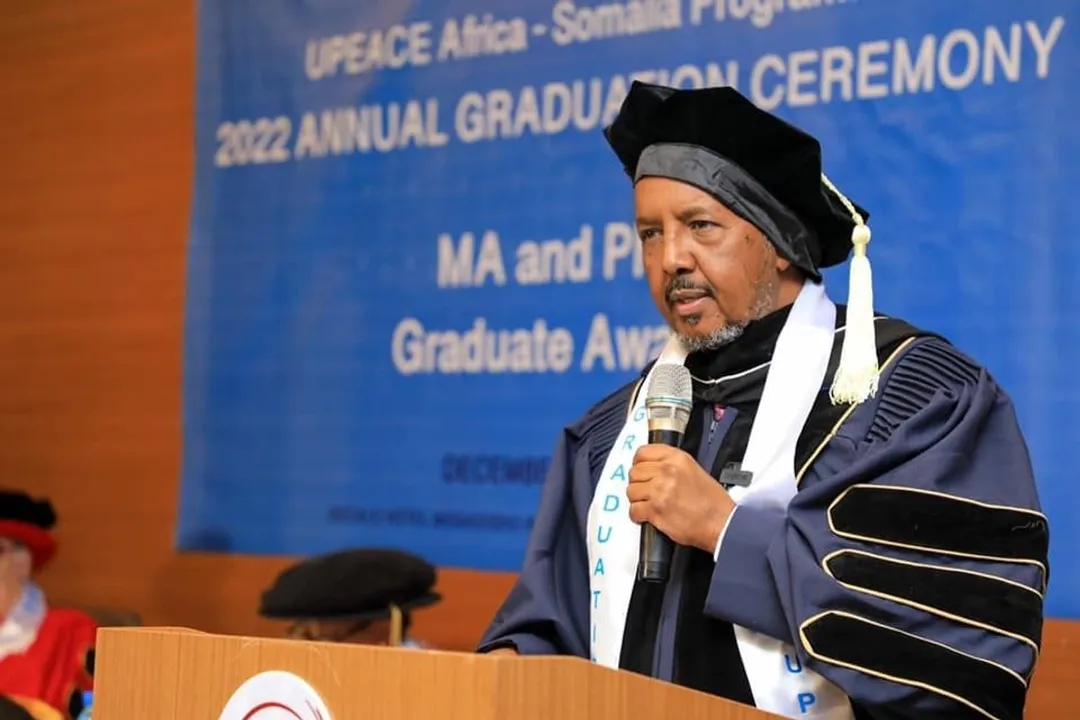

The cabinet recently approved the establishment of the nation's first National Higher Education Commission, chaired by former presidential candidate Abdinur Sheikh Mohamud.

Backed by the National Higher Education Act, the first legislation providing a framework for regulating universities, the commission oversees 130 registered institutions.

Technology has become central to this transformation. The Education Management Information System (EMIS), introduced in 2016, tracks enrolment and performance data. Its higher education counterpart HEMIS, launched in 2023, has already registered 248,000 graduates and 200,000 current students.

"HEMIS has been in existence for almost a year," says the education minister.

The system enables credential verification, a crucial step for Somali students seeking opportunities abroad.

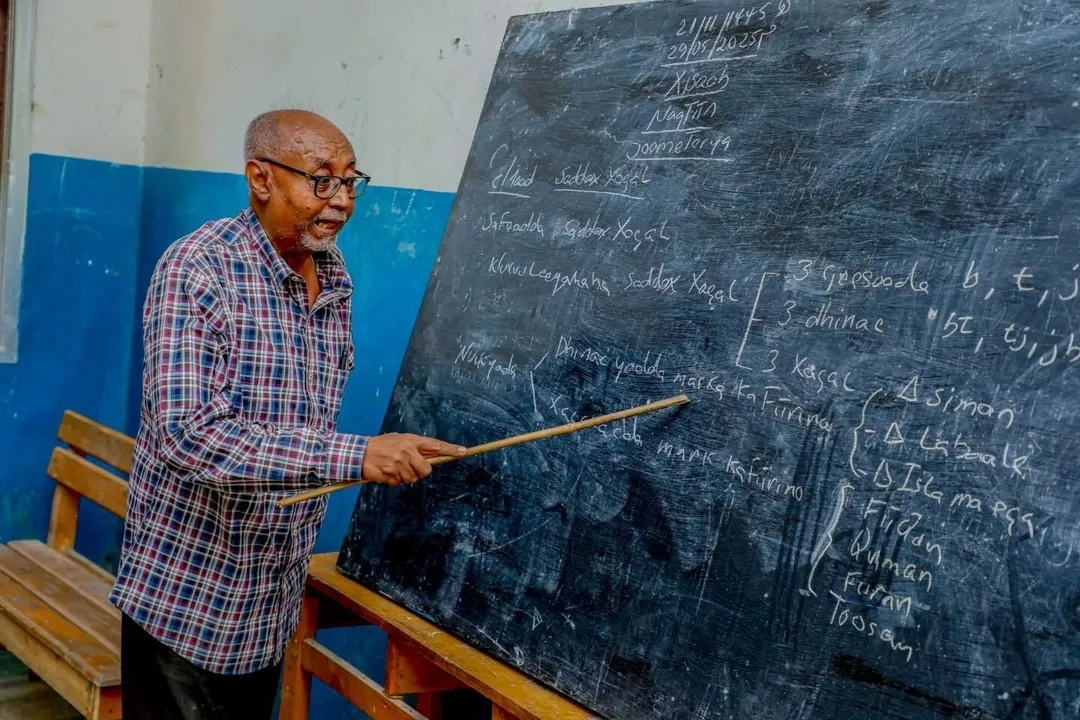

Dr Hussein Ahmed Salad, who has taught at all education levels in Mogadishu, envisions a broader impact.

"We have come a long way, and there is massive belief in our education system. Education reforms have boosted the validity of our academic certificates since we have systems such as HEMIS that enable tertiary institutions to verify documents, thus allowing our bright students to access education everywhere," he tells TRT Afrika.

The reintroduction of standardised Grade 12 exams in 2015 started with 7,000 participants. By the 2024-2025 academic session, that number had reached 39,000, including students in Las'anood who were writing exams for the first time in three decades.

Education as liberation

The government's military offensive against Al-Shabab terrorist group since late 2022 has helped build a resistance to terrorism that has since translated into higher enrolments in educational institutions.

In Harardhere, the education ministry distributed textbooks and digital tablets in collaboration with UNICEF and the AU Mission in Somalia as children returned to classrooms after a decade and a half.

A pre-university foundation year covering Somali, Arabic, English and civic skills, including conflict resolution, prepares 10,000 students annually for higher education.

The education ministry insists this represents essential preparation for academic success rather than an additional year of study.

Gender equity has also risen. Female participation in Grade 12 examinations rose from 26% in 2015 to 42% this year. In September 2024, the education ministry extended scholarships to 3,000 girls for training in midwifery, nursing and teaching through vocational programmes.

Accelerated basic education programmes help children who began in Islamic schools transition to the formal system.

A unified national curriculum and textbooks for primary and secondary schools, alongside national certification for primary education, create coherence where chaos once reigned.

The road ahead

"We ideally require between 80,000 and 120,000 teachers; we currently have around 35,000 teachers," says Dr Hussein.

Education minister Farah Abdulkadir says Somalia's uncompromising commitment to furthering education is something that will drive numbers.

"We will never return to our past," he says. "We need to have faith in our education, our teachers and policies, because no nation can make progress without a strong and stable higher education system."

The transformation from ruins to renewal through education continues.

Comments

No comments Yet

Comment